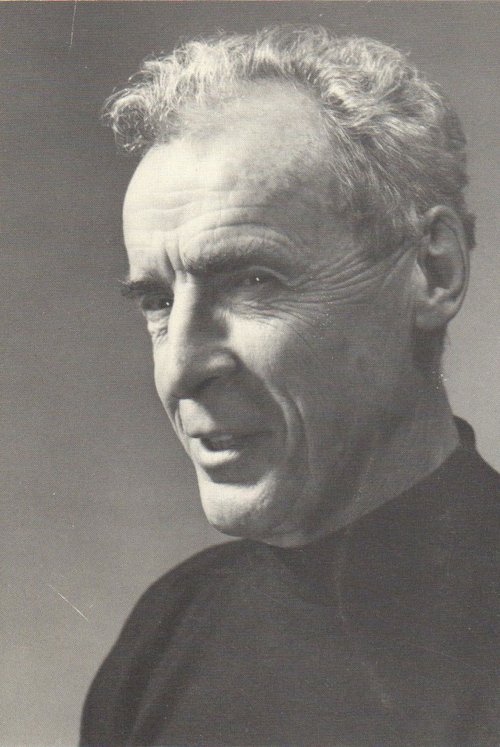

Harold Haydon

BIO

b. 1909 – d. 1994

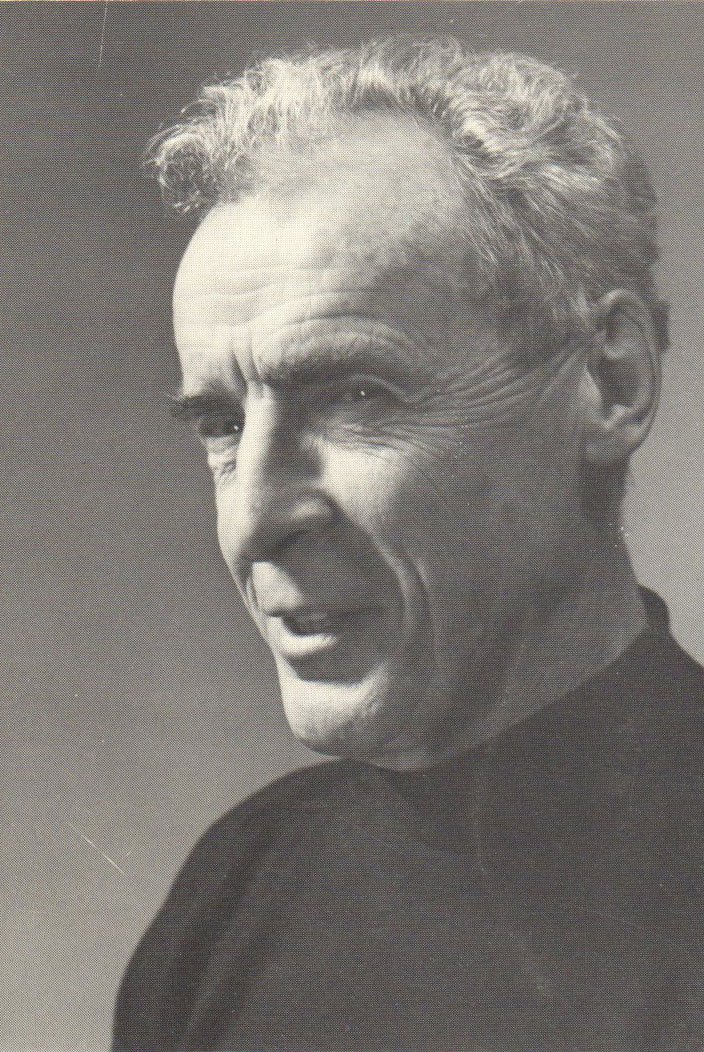

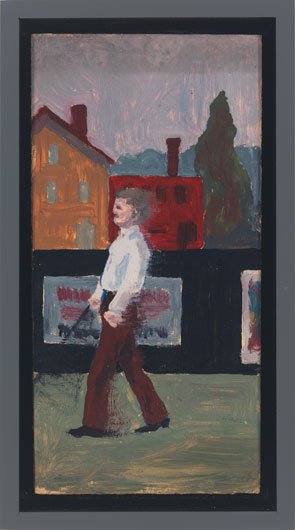

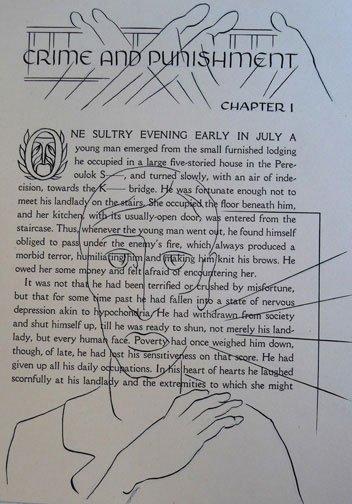

Harold Emerson Haydon was born in Fort William, Ontario, Canada in 1909, and he died in Chicago in 1994. He came to Chicago with his family in 1917, earning a PhB from the University of Chicago in 1930 and then an M.A. in Philosophy in 1931. While continuing with post graduate study in aesthetics, he also took art courses at the School of the Art Institute. Returning to Chicago. he focused his career on working and teaching in the Chicago area. First he taught arts and crafts at George Williams College from 1934-44, and then began teaching art at the University of Chicago from 1944-75, becoming Professor Emeritus of Art in 1975. He was also Director of the Midway Studios at the University of Chicago from 1962-75. Haydon took over as art critic for the Chicago Sun Times from 1963-1985. From 1975 to 1981 he also taught mural design, at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago and was an Adjunct Professor of Fine Arts, 1975-1982, at Indiana University, Northwest Campus, in Gary. Primarily a painter, Haydon also designed and constructed murals in glass mosaics and ceramic tile, designed stained glass windows, created metal and plastic mobiles, and made polyplane paintings on glass. He began exhibiting paintings in the U.S. and Canada in 1933 and was active in artists organizations starting in 1945. Author of “Great Art Treasures in America’s Smaller Museums,” 1967, and numerous articles, Haydon was also an illustrator.

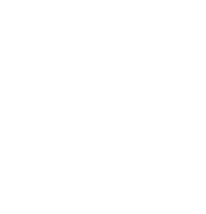

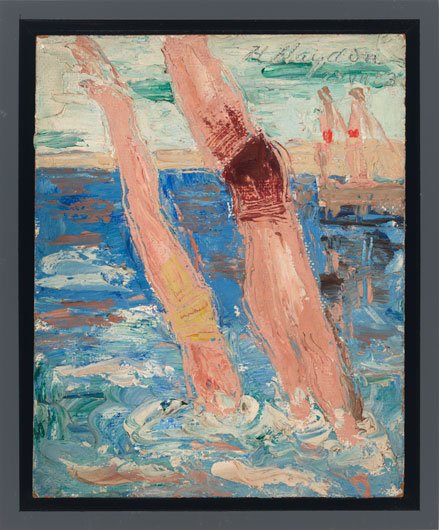

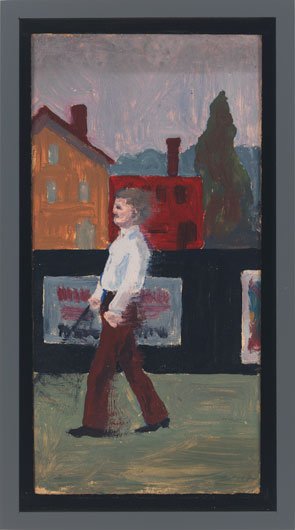

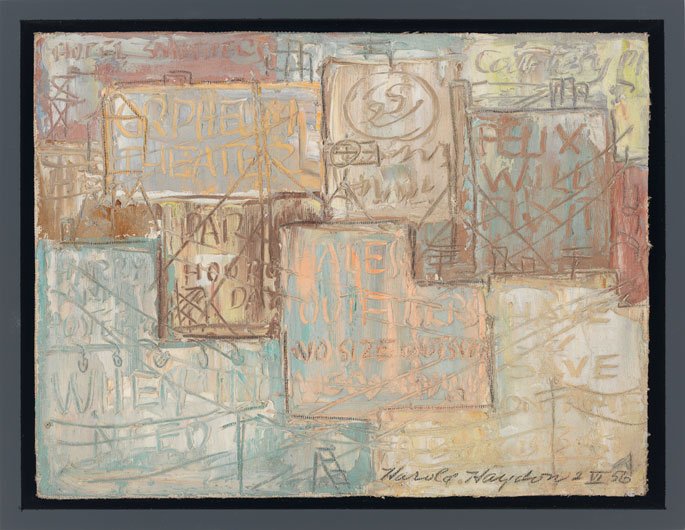

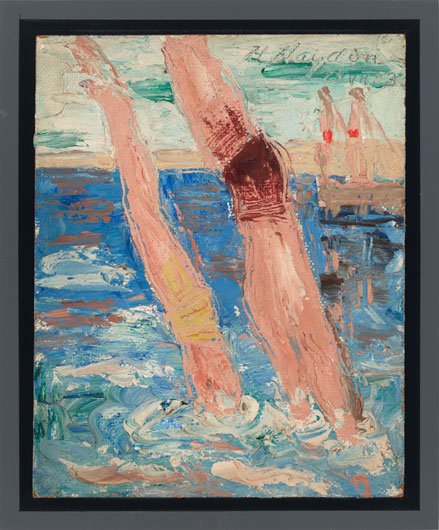

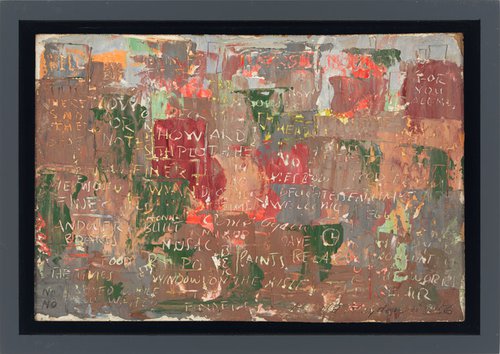

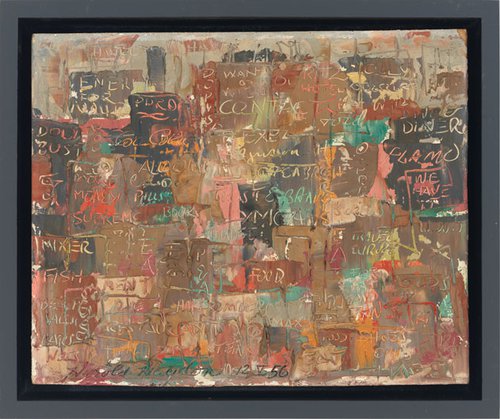

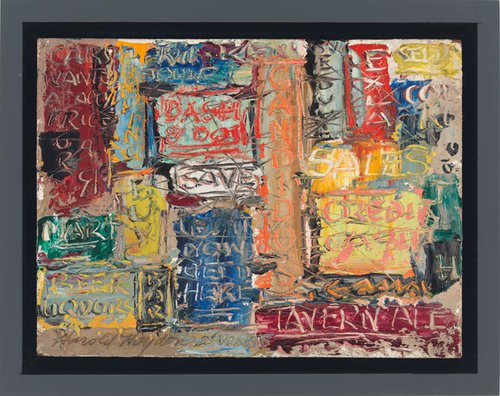

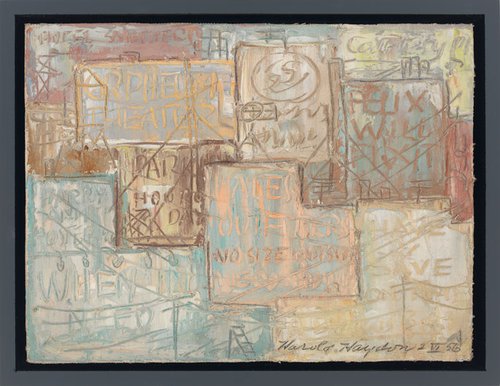

For over 50 years, from 1931 until his death in 1994, Harold Haydon pursued a unique compositional theory, which he called “binocular vision.” He saw it as revolutionary, a radical new approach to painting composition just as significant as Cubism. He hoped, of course, that artists would rally around his invention and even feared at the beginning that it might be stolen from him.

In normal vision, all images are seen double except in the plane of focus where the images received by both eyes coincide. The varied, overlapping, and transparent doubled images provide a fascinating new complexity of composition. More significant from the plastic point of view, the effects of normal vision with two eyes vastly intensify the effects of three-dimensional space. While the basic impulse of these paintings springs from careful observation and analysis of the facts of natural vision, the pictorial result is highly subjective and interpretive, since the visual field is different for everyone and the intensity of the images from either eye vary and shift.

Haydon exhibited his work often and wrote descriptions of it. He gave lectures and demonstrations. There were press reviews of his exhibitions and illustrations of his binocular paintings in the media. Having been a member of the major artists’ organizations and having held office in several, Haydon was active in the Chicago artists’ community. Clearly he was well known and liked, and other artists knew his work. But Haydon was always disappointed by the response he received to his binocular vision theory. In a 1951 letter to an old friend he lamented that he had “yet to see anything but superficiality and misunderstanding on the part of art critics.” Part of the problem may be that while he was an able communicator and described his work well, he never fully explained how he derived the concept.

Haydon sought a creative approach to the elements of time and motion. In doing so, he focused on two points of special interest, and they both had to do with the true effects of vision. One was binocular vision and the other was retinal afterimage. Each grew out of his fascination with discovering the true nature of the physical world. He had delved into the inscrutable world of the new physics, as well as the philosophical discussions that emerged from it, and became convinced that art needed to revise its representation of the world. Interestingly, with all of his studies of new scientific discoveries, the primary antecedent to Haydon’s binocular vision painting came from Leonardo da Vinci’s notes on the subject and his description of how our eyes use it to obtain stereoscopic depth. Unfortunately, in Haydon’s view, “people continue to see the world from the “one-eyed” point of view, neglecting the doubling of images on the retina.”

Exhibitions

- "Nuth'n to Hyde" Gertrude Abercrombie and the Hyde Park Ethos, 1935–1975 June 20 - August 2, 2025

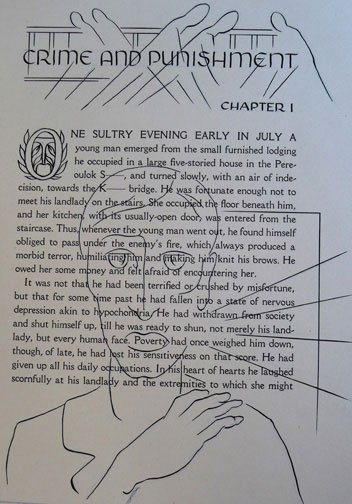

- Harold Haydon Crime & Punishment February 19 - March 27, 2010

- Harold Haydon Binocular Vision September 14 - October 20, 2007