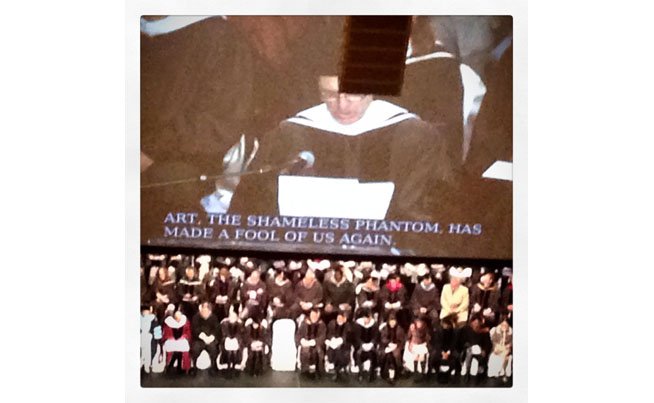

Albert Oehlen delivers commencement address at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago

June 9, 2015

CHICAGO – The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), one of the nation’s leading art and design schools, welcomed contemporary artist Albert Oehlen to deliver the school’s 149th commencement address on Monday, May 11, 2015. The complete text of the speech is listed below.

“Dear friends, artists, architects, designers, performance artists, teachers, preservationists, art historians, administrators, parents, parents of administrators, and friends.

A few years ago I had the honor to do studio visits at SAIC. I know what your school looks like from the inside. I met a lot of interesting people. Young women and men, who inspired, amused, frightened and impressed me. Although this kind of teaching is very different from the way I taught in Düsseldorf for example or from the kind of art-education I enjoyed as a student in Hamburg, the question you ask yourself as a teacher remains the same. What do they want from me? As a teacher you also wonder: Is the student worrying about that same question?

As a student, I had it much easier. The Professor, as an artist, was my idol. I adored him, then copied him for a while and then proceeded to doing always exactly the opposite of what he would do. And now should be the time, where I can see myself as the idol, who is stomped down into the bottom of the garbage can. But I couldn’t really expect that here. Instead I stood in front of the newest works of a student and had to say something about them in the shortest amount of time. To do that, I had to find out what he or she actually wanted to do. Because that’s the only criterion to measure the success of someone’s work. And then the next problem: Everyone wants something different anyway. Are there even any rules that I believe in? That I would dare to suggest to a student as valid maxims? Hold your brush straight! The hairs of your brush should always point away from your body and onto the canvas! Keep your studio tidy. Don’t drink Red Bull. I always had to imagine, how I would have reacted to that as a student. How do you teach something without rules, the condition of which you believe should be total freedom and multiple choices? The artist, equipped with freedom at least on a juridical level, isn’t so free. Psychologically, culturally, she is full of inclinations and fetishes.

First you ask one question: Did you do that on purpose? Cause that’s what it’s all about. It’s not our appearance, our education or wearing super-precise wrist watches, that separates us from wild animals. It’s only our free will. And the thing that happens between intention and achievement is what you call artistic practice. If these students only knew what’s going in my studio!

Now I just spent an hour on the sofa with my head in my hands brooding. I make myself a coffee. No effect. Waving 5 kilo dumbbells, I pump the caffeine into my bloodstream. Now something has to happen! Just a little brush-mark could save everything. A stroke with the spray-can. I am a genius! I would be a genius, if I hadn’t just leaned against my painting-trolley. There’s paint on the sofa. This has to be cleaned first. I’ve got it: I take the aluminum ruler and draw a long line straight through the whole picture. I divide the picture into a good and a bad half. Genius! This picture no longer paints, it is painted. Like bell clappers, the vanishing lines protrude from the swinging perspective bucket. A demon in an obscene posture operates this instrument of torture. Bourgeois banality, work thought through, one day you will swallow your own paws without noticing it. Various souls represent the picture: souls that are forgotten, souls for the rotten, souls for cleaning up, souls for being eaten. However, the souls are not painted completely, and so appear grey, hollow and lukewarm. One would like to send them away, chasing them with the lash.The air in this painting seems to be folded like small envelopes, as if they thought to contain documents and carry them away. But: If I did that, I’d be finished straightaway and then I’d really think I was a genius and I’d just be tempted to try and repeat that and then I’d end up painting bad pictures and then I’d be ruined. Back to the sofa! And that’s how it goes, on and on, until even hollering along to ‘London Calling’ and ‘Born in the USA’ at the same time can’t lighten my mood any longer. And now I’m supposed to tell this young student, don’t copy from Lady Gaga photos. Don’t mix oats into your paint. Don’t set fire to your painting.

I’m a painter de brocha fina as the Spaniards would say. That’s a bit misleading, but you know what I mean. What really separates us from a house painter is freedom. And that’s the subject of my talk today. From my point of view freedom is the only really interesting (or relevant) topic of art. Of course you can all do whatever you want, but freedom is my subject matter. You can deal with the color red, with skulls, with TV or your own identity or the identity of others. But if you want it to be worth anything, the results should be different, to the extent that they come from an artist, whose privilege it is to be granted absolute freedom in the execution. Which means we are technicians of freedom. That this kind of freedom doesn’t really exist isn’t the subject of my talk. Rather, it’s about the way we make use of this concept. Now it gets serious.

Once, when I was invited to give a talk in a museum in Frankfurt with Julian Schnabel, I saw Lou Reed come in. He sat down in the second row and went to sleep the moment I opened my mouth and only woke up from my friends applauding for me at the very end. So, I have a very good reason to worry about the success of this speech. Still, I kind of wish Lou Reed were sitting here now, snoring loudly.

So, I was saying: We are technicians of freedom. What does that mean? We sleep till 11, smoke, drink, talk jibberish and wear berets. Others can do that too. But the only thing that others don’t have is the freedom we have in our work. We enjoy this ideal situation of having a non-alienated occupation. That’s great for us. Who gives us this freedom? We just take it, because we have appointed ourselves as artists. But this also brings with it a duty to make useof our privilege. And that’s exactly what we’re doing: We paint on lead, let others paint for us, we dig holes, dress up as ice-cream sellers etc. No practical joke that doesn’t have a place in art.

In the universal search for a standard there is something tragic, a sort of cosmic sadness. Phantom inspirations, deadlocked in brackets, yell: I am on this earth only to serve as material for doctors, cannon fodder, horses and students (of horses).

The fire must never and will never go out. A world of insanity, despair, of the measurement of the decline of genuine meteoric material, for many the primordial stone of the losers. Could the real-time visions of a Dr. Panfilo, the mad public-aid doctor of the long summer evenings, have hit us any colder?

That’s how we imagine the avant garde. And that’s what avant garde is. Sometimes. But the problem is that the external world, or that which thinks of itself as the ‘real world’, is well prepared for this. It feels as though we’re breaking down doors that are already open. Are we just clowns for a society that knows exactly what actually counts? Where’s the beef? What became of good old provocation?

I don’t know when exactly, some time in the 60s, the Austrian artist Christian-Ludwig Attersee announced, in order to promote his upcoming show, that he was going to pump up a toy poodle toten-times its original size. The reaction to this was not an honorary doctorate,but a protest demonstration by animal-lovers, which made the actual performance redundant. No balloon-dog.

These kinds of laughs are denied us nowadays. They’re done. Political symbols, pornography, cruelties, and tastelessness might still provoke, but they are boring and reactions to them are foreseeable. Parsival, van Gogh, GG Allin. When will we smash through the bottom of the cask? The beauty of the poodle example is that it shows what confidence the artist once enjoyed. This doesn’t seem possible anymore. Everyone is prepared for anything. There is this idea of the new, the current, the relevant. Painting is more colorful, sculpture is a diss on the viewer and everyone is digging around in the 20-year-old internet. How are you supposed to do anything new, if everyone knows what ‘the new’ looks like? How do you impress a curator, who has long outrun Guy Debord, but sadly can’t see with his own eyes. The museums accept any old subject-lump, if it just meets the criteria for time-real material.

Give them a skateboard.

The term quality is a paper tiger. When a person without an arse says: But you can’t even sit on that chair…Boredom! The most boring person will tell us: that’s boring. It doesn’t make any sense. Where’s the light. I can’t see it. Or: I won’t publish this. Or: You can’t sleep here. They’ll tell you: That won’t stand. It’ll fall over. Or: That’s not the way it works. That doesn’t have any structure. Yessir: I don’t have structure. I won’t, I can’t let that happen again.

It is the world of the superintendent, a world that doesn’t want to burn, does not explode, and doesn’t want to go down. It is reality in vertical form, displayed with the didactic aim of wearing us out. I won’t, I can’t let that happen again.

We will refuse the game. We will refuse a statement. And that’s when we call the shots again. Resistance and Misunderstandings are our nourishment. We can make a weapon out of the handicap. The really New doesn’t look very good. We’re sorry. And the oldest stuff wears the newest garments. Art, the shameless phantom, has made a fool of us again. Every good painting, every square wheel, every backwards running video, is a slap in the face of the superintendent. The trickling upward theory.

What makes it so unpleasant to see bad art? That you understand it. You can’t find something ugly that you don’t understand. It should challenge you and create a happy expectation instead. The horrible thing about bad art is that you know it well. Because it is part of us. The art you find most awful is the stuff you once had in your head. Ideas you discarded. Abandoned experiments…Wrong tracks, from which you just about turned the corner. A misery you don’t want to be reminded of. But we have one ally: tedium. Tedium drives us on, towards the unknowns, the new. We carry on running. It’s bad art that keeps the whole thing going. It generates the money that nourishes the whole art-market. Bad art is the soil in which we bury our masterpieces. Bad art trains our taste. Armies of mediocre, good-humored,talented ignorants produce a continuous reevaluation of our achievements.How can I make my point clearer? How does this look over a bed? What if I put little wheels on it? Not one of all the futile experiments is excluded.Every thinkable combination of materials and ideas has to be executed. Like a sticky liquid it fills all the gaps and holes. There is no escape. No defoliating, no dehydration, no sobering up can help us. We see this rubbish everyday.

But transcending everything is the arrogance ofthe material with which you work, which could be paint, stone, film, sound, a thought. This is what we should care about. This is what cares about us. To learn at SAIC is to learn to win.

At the next Lou Reed gig, we’ll be sleeping.”