Isobel Steele MacKinnon

BIO

b. 1896 – d. 1972

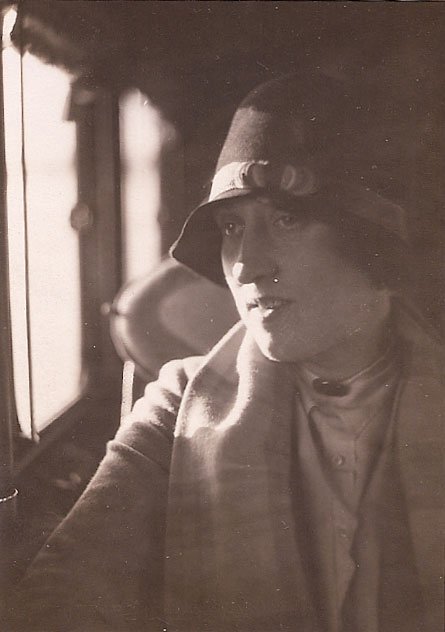

Isobel Steele MacKinnon’s adventures as an American artist living and working in Europe echo those of many other expatriates of the epoch. MacKinnon and her husband Edgar Rupprecht were, by the time they left Chicago in 1925, both well-established figures in Chicago’s art world and especially in Saugatuck, Michigan, where they taught at Ox-Bow Summer School. What the couple encountered in the studio of German artist Hans Hofmann would rock the impressionist foundations of their artwork and transform them into committed modernists.

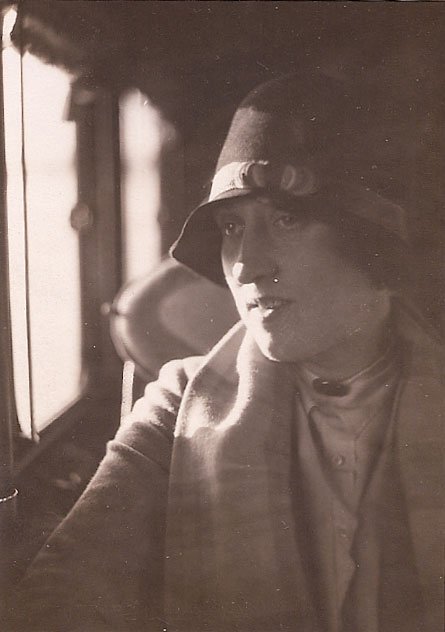

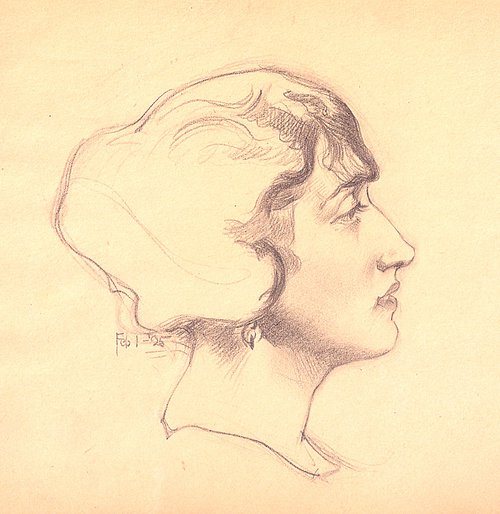

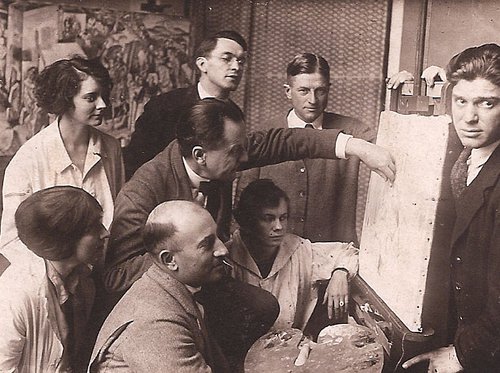

Hofmann’s Munich-based school was a magnet for foreign students starting after WWI ended and stretching until Hofmann left Germany in the early 1930s. Indeed, over the period of four years during which Steele and Rupprecht worked alongside Hofmann, from 1925 to 1929, their fellow students included renowned abstract artist Vaclav Vytlacil and painter Worth Ryder, the artist who would invite Hofmann to teach in the U.S. for the first time in 1930. A small, elegant, realistic profile drawing that Rupprecht made of MacKinnon in 1925 makes fascinating contrast with the work she produced while in Europe. In Chicago, her approach had been as conventional as his, but under Hofmann she took to the new ideas with startling ease, absorbing his “push and pull” spatial concept and his deep investigations of the compositional consequences of hot and cold colors.

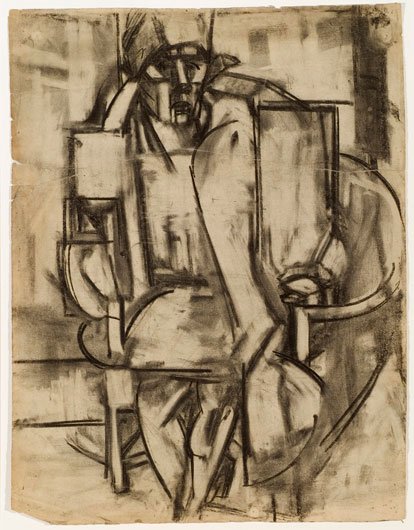

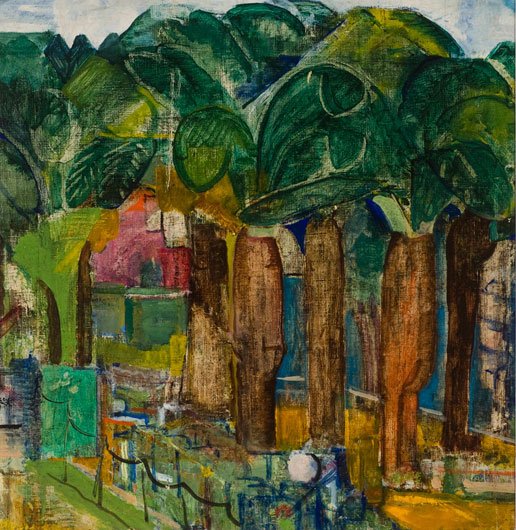

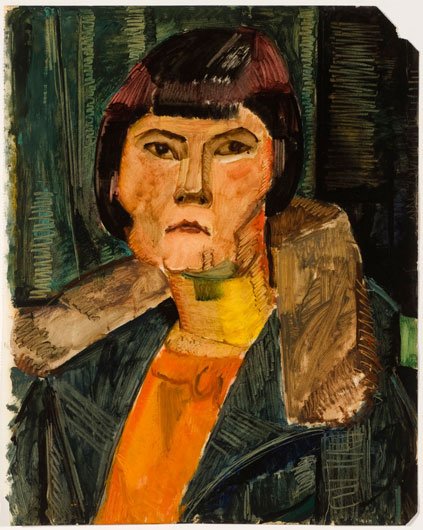

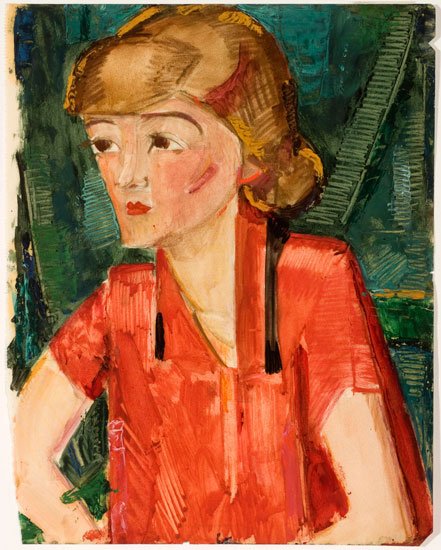

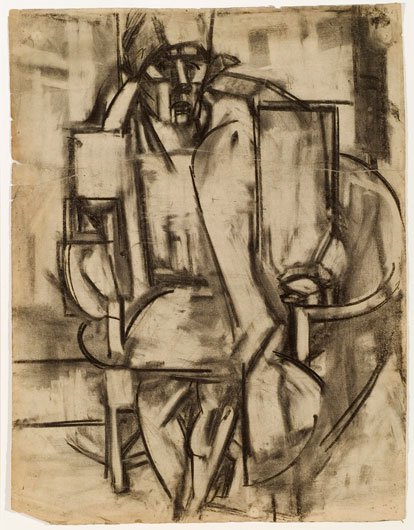

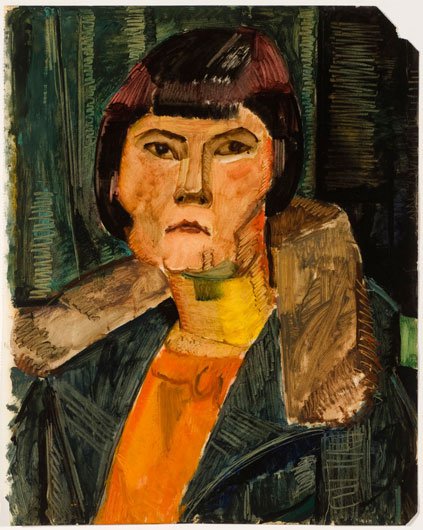

The portraits of German and other expat sitters made at the time have the analytic angularity associated with Hofmann, drawn and painted with a palpable power and sureness. Some resemble expressionists like Kokoshka or Meidner. More radical than her portraits, Steele’s slashing charcoal gesture drawings of figures are sometimes exceptionally abstract, hauntingly presaging the abstract expressionist women of De Kooning. These works represent an artist in the throes of letting herself loose, shaking off the constrictions of academicism, experimenting with vital energy and an unwavering hand.

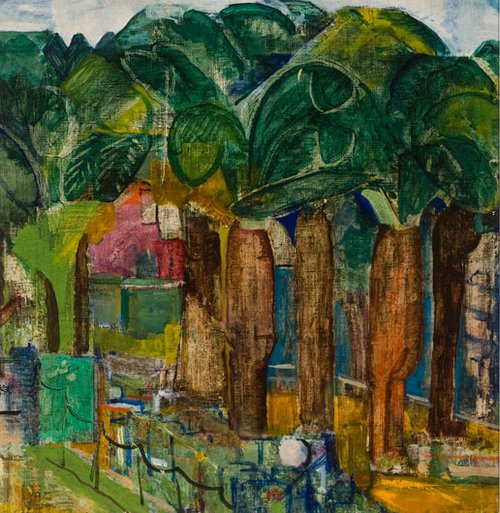

During their European summers, Steele and Rupprecht traveled with Hofmann. Steele had quickly risen to become his premier student. On Capri and St. Tropez, she painted bright, abstracted landscapes, often based on carefully plotted line drawings. The warm environs in some cases drew out her old impressionist tendencies, but in the most advanced of these she blocked colors into shapes and patterns that suggest Hartley or Avery or in some Jan Matulka. In one drawing, probably from Paris, she has sculpted the trees into architectural forms.

After their sojourn, which extended from their studies with Hofmann to several years as active artists in Paris, Steele and Rupprecht returned to Chicago. They were rejuvenated, heads full of new ideas, portfolios brimming with the work they’d done. When WWII was over, Steele began a long and fruitful teaching career at the School of the Art Institute. From this post she introduced many young artists, from Jack Beal to Tom Palazzolo, to Hofmann’s concepts at the identical time that he was teaching the future abstract expressionists of America from his schools in New York and Provincetown.

Exhibitions

- Ox-Bow Centennial : Historic June 26 - August 21, 2010

- Isobel Steele MacKinnon Weimar Portraits Riviera Landscapes March 28 - May 3, 2008

- Benjamin Seamons New Paintings March 28 - May 3, 2008